Was Finding An Alzheimer's Cure A Lie?

- Our Say On Science

- Aug 26, 2022

- 4 min read

By: Sophia Li

“You can’t cheat to cure a disease. Biology doesn’t care.”

Dedicating your life to research takes a lot of commitment, but what most don’t know is the process behind discovering something no one else has. People spend their days and nights in a lab to unearth the unthinkable. But what if someone told you that it was all a lie? That the research that one spends their days and nights for, was a lie?

Matthew Schrag, a neuroscientist and a doctor at Vanderbilt University first uncovered supposed falsified research on Alzheimer’s disease. The worst part was that this research paper was the fundamental paper of new and upcoming Alzheimer’s research, meaning this paper set us back almost twenty years. “The Nature paper has been cited in about 2300 scholarly articles—more than all but four other Alzheimer’s basic research reports published since 2006.” (Piller). Not only does this article set us back in time, but it also sets us back in money. The NIH (National Institute for Health) funded about “$287 million in 2021” for amyloid and Alzheimer’s research. (Piller).

All Alzheimer’s therapy medications have a 99% fail rate. Why? Because we are treating the wrong problem. Every single Alzheimer’s therapy trial has failed. All of them. The false data produced was the basis of most therapy medications, and we got it all wrong. My first thought was, what? I quite literally had no words. Then, I got curious.

Around the year 1905, researchers like Alois Alzheimers found dark plaques that surrounded neurons in patients who had Alzheimer's, but it wasn’t known as Alzheimer’s back then. It was just patients who died from memory loss and dementia. The dark spots looked like some form of amyloid protein. It wasn’t until the 1980s that we figured out that the dark plaques were made up of some type of amyloid-beta protein. In 2006, Sylvain Lesné, a neuroscientist at the University of Minnesota, isolated a new oligomer species from the amyloid beta protein: Aβ*56, (amyloid-beta star 56). He and his team injected this protein into mice, and “their ability to recall information plummeted.” (Piller). Thus, a correlation between Aβ*56 and Alzheimer’s was born.

However, suspicions were raised when Matthew Schrag got a call from a colleague to review possible scientific misconduct. Cassava Sciences produced a drug called Simufilam that would repair a “protein that can block sticky brain deposits of the protein amyloid beta (Aβ), a hallmark of Alzheimer’s.” (Piller). He was concerned regarding the research related to the drug because it may have been tampered with. After many hours of researching, Schrag worried about the original, ground-breaking article published by Lesné. “Aβ*56 itself does not seem to exist. Other researchers had failed to find it even in the first years after the 2006 publication…” (Lowe). Science asked for image consultants and microbiologists, Jana Christopher and Elisabeth Bik, respectfully, and noted that these images were “shockingly blatant” and “highly egregious.”

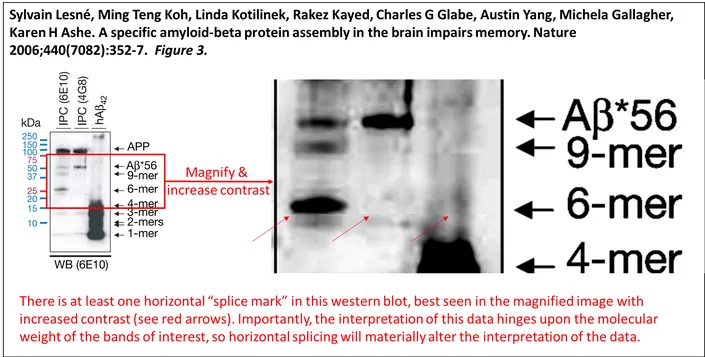

Reading articles about this scandal can only go so far. So I decided to take this situation into my own hands and look at PubPeer, a collaborative space where people can criticize others’ research papers while staying anonymous. I looked at what others wrote for the original article that raised concern, A specific amyloid-beta protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. And wow, there was overwhelming evidence that Lesné had cut and spliced evidence as shown in the figures, right below this article. For example, look at supplementary figure four. Lanes 2-4 and 5-7’s top bands are almost identical, as shown by the merging of the two pictures, the yellow color is identical areas. In the next figure in question, figure one, if you look closely, you can see horizontal lines, but transparent, and it looks unusual. The same problem with figure three, there are definite splice lines in the western blot. Those are horizontal splices, which are unnatural, definitely suggesting they have been tampered with. Those that Lesné had worked with all said that he was very hardworking, however, he had all authority with the pictures. The articles that his colleagues wrote without him all seemed to show no red flags in tampering.

How did researchers that used his paper not have known if the data was falsified? Wouldn’t they have tried to replicate the research? Well, first of all, that takes a lot of time and money to replicate data. It is also difficult to “publish results that invalidate previous work in academic journals.” (Guenot). However, as said before, specific to this case, there is no Aβ*56 found. But what happened to the peer review? How did it pass? This is because the scientists who are peer reviewing probably do not have in mind the fact that this could all be fabricated. Derek Lowe, a researcher specializing in schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, etc. said “It’s not the way that we tend to approach scientific manuscripts… There is a good-faith assumption behind all these questions: you are starting by accepting the results as shown.”

Why did he falsify data? I honestly have no clue, but I do have speculation. I believe it’s probably that he just wanted a groundbreaking paper so much that he was willing to falsify data like that. Publishing papers like that will give one such an advantage in getting grants, high-level academic jobs, and winning awards. Maybe his ambition got the better of him, leading Lesné to do the things that he did. Kind of reminds me of Macbeth, when too much ambition leads to his demise, Lesné might be slowly arriving at his: being caught. But, that’s just what I think. He may have had a different motivation, maybe he just wanted his hypothesis to be supported by the data. Maybe he didn’t like to be proved wrong. We may never know. But what we do know is that we have wasted two decades and millions - if not billions - of dollars on Alzheimer’s research.

Comments